Week 4 practical

Simple key- and button-press responses

The plan for week 4 practical

This week we are going to look at code for a simple grammaticality judgment experiment. Remember, the idea is that you can work through these practicals in the lab classes and, if necessary, in your own time - I recommend you use the lab classes as dedicated time to focus on the practicals, with on-tap support from the teaching team.

A grammaticality judgment experiment

By this point you know enough of the basics of jsPsych and javascript to work with a simple experiment. We’d like you to download and run the code we provide, look at how the code works, and then attempt the exercises below, which involve editing the code in simple ways. In the next practical class you’ll get a chance to build the experiment yourself before looking at example code from us.

Getting the code

You need two files for this experiment, which you can download through the following two links:

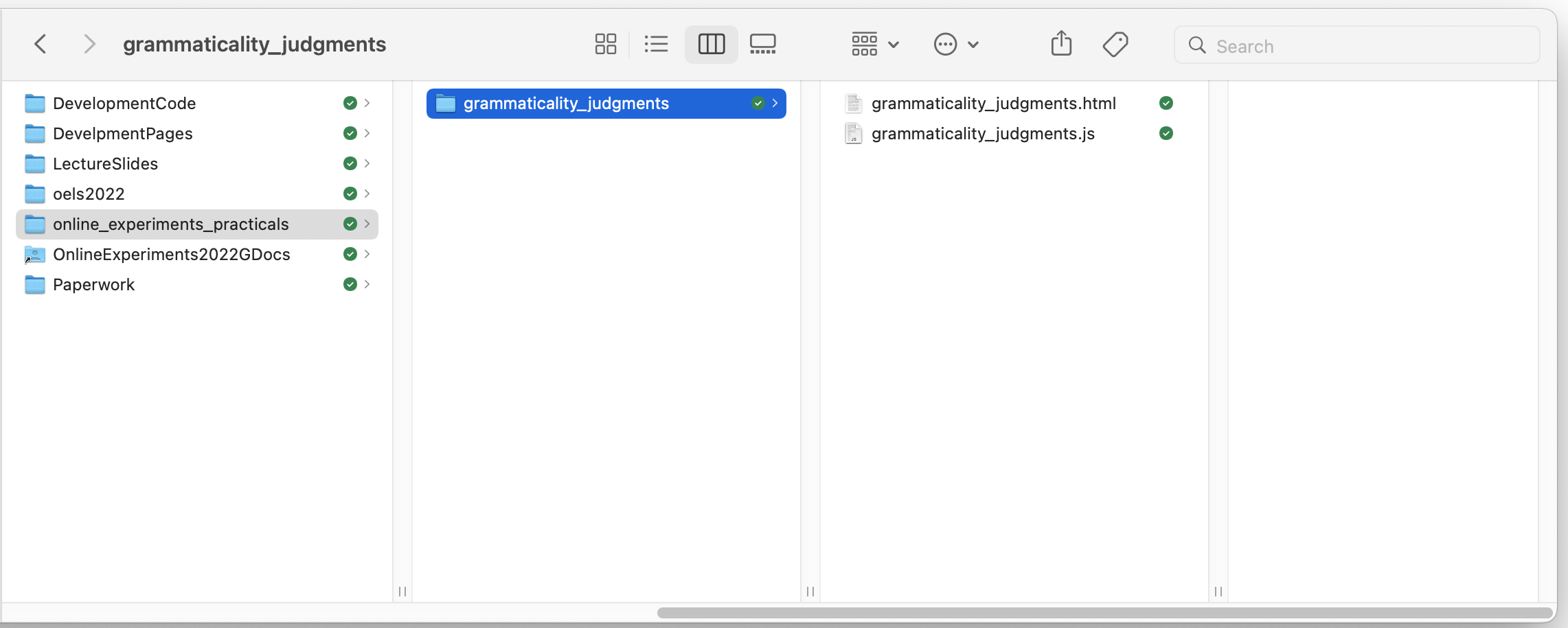

The code makes some assumptions about where you will save it - you can change that if you want but then you’d have to edit the code so it is looking in the right place, so it might be simpler to copy my directory structure. If you haven’t already, create a folder (also known as a directory) called e.g. online_experiments_practicals. Then create a new folder inside the online_experiments_practicals folder called grammaticality_judgments, and move the two files you just downloaded in there. So if you do that all correctly you will have a folder called online_experiments_practicals that has a single sub-folder called grammaticality_judgments, containing the grammaticality judgments code. On my mac it looks like this.

The idea is that every week you will add a new subfolder to the online_experiments_practicals folder containing new code for a new experiment.

This code should run on your local computer (just open the grammaticality_judgments.html file in your browser) or you can upload it to the jspsychlearning server and play with it there, using the same sort of directory structure - it needs to be in public_html, e.g. if you have exactly the same directory structure on the server then the code would be in public_html/online_experiments_practicals/grammaticality_judgments/, and the URL for your experiment would be https://jspsychlearning.ppls.ed.ac.uk/~UUN/online_experiments_practicals/grammaticality_judgments/grammaticality_judgments.html (where UUN is your student number, s22… or whatever). Or you can go to https://jspsychlearning.ppls.ed.ac.uk/~UUN/online_experiments_practicals/ and navigate to your code there.

First, get the code and run through it so you can check it runs, and you can see what it does. Then take a look at the HTML and js files in your code editor (we are recommending Visual Studio Code).

Walk through the code

This is probably one of the simplest types of experiments you could build. It has 4 grammaticality judgment trials, where participants provide a keypress response: y or n for “yes, this sentence could be spoken by a native speaker of English” or “no, it could not”. Note that is slightly different from what Sprouse (2011) does - he asks people for a numerical response rather than a simple yes-no, we’ll come to that later.

There is also a little bit of wrapper around those 4 trials - a consent screen where participants click a button to give consent and proceed to the experiment, some information screens before the experiment proper starts, and then a final screen where you can display debrief information, completion codes etc to participants.

You will see that grammaticality_judgments.html doesn’t have much in it - all that does is use the <script>...</script> tag to load a couple of plugins via the CDN plus the file grammaticality_judgments.js.

The bulk of the code is in grammaticality_judgments.js. You will see that that code includes comments - these are bits of text that are enclosed in special markers so that the machine running the code ignores them.

/*

This is a javascript block comment - the interpreter ignores this stuff in between the slash-star

and the star-slash, it's for you to read, although note that anyone looking at the source code of

your experiment will see these comments, including any curious participants!

*/

// Individual lines can be commented out like this, with a double slash at the start.

Those comments in the code are intended for you to read, to explain what the code is doing. But I’ll also add some explanation here.

The first thing that happens in the code is that we initialise jsPsych, as in the tutorials you have seen up to this point. We also tell it to show the raw data on-screen at the end of the experiment (using the on_finish parameter of initJsPsych). Obviously in a real experiment you would save the data rather than just showing it back to the participant, we’ll show you how to do that later in the course!

var jsPsych = initJsPsych({

on_finish: function () {

jsPsych.data.displayData("csv");

},

});

The code then lays out the grammaticality judgment trials. Note that just because they come first in the javascript file (e.g. before the consent screen, which is later in the code) this doesn’t mean they will be the first thing the participant sees - the experiment timeline controls what participants see when.

Each judgment trial involves showing the participant a sentence and getting a single keypress response from them, which we can achieve using the html-keyboard-response plugin from jsPsych. Details of the options for that plugin are in the jsPsych documentation. We are using the stimulus parameter for the sentence the participant is judging, prompt reminds the participant what they are supposed to be doing, and choices shows the list of keyboard responses they are allowed to provide - in this case we only accept y or n keypresses, so any other keypress is ignored. So the code for one judgment trial looks like this:

var judgment_trial_1 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus: "Where did Blake buy the hat?",

prompt:

"<p><em>Could this sentence be spoken by a native speaker of English? Press y or n</em></p>",

choices: ["y", "n"],

};

The only slightly fancy thing in there is that in the prompt I am using some HTML tags - the <p>...</p> tag to put the prompt in its own paragraph (it vertically separates the prompt from the stimulus a bit, which I think looks better) and also the <em>...</em> tag to make the prompt in italics (again, to visually separate it from the stimulus sentence - em stands for emphasis I think). If you want to know what the prompt would look like without those tags, feel free to delete them and reload the experiment to find out.

The code defines 4 such trials, inspired by the type of sentences used in Sprouse (2011), all using exactly the same template.

That’s basically the only interesting part of the code! But we also need some preamble for the participants. Most experiments start with a consent screen, where participants read study information and then consent to participate. I include a placeholder for this consent screen using the html-button-response plugin - you see the consent information and then click a button to indicate that you consent. The code for that looks as follows:

var consent_screen = {

type: jsPsychHtmlButtonResponse,

stimulus:

"<h3>Welcome to the experiment</h3>\

<p style='text-align:left'>Experiments begin with an information sheet that explains to the participant\

what they will be doing, how their data will be used, and how they will be remunerated.</p>\

<p style='text-align:left'>This is a placeholder for that information, which is normally reviewed\

as part of the ethical review process.</p>",

choices: ["Yes, I consent to participate"],

};

You will notice that the stimulus parameter here is quite complicated - it includes some HTML markup, including tags for headers (<h3> and </h3> to start and end a header), and paragraphs (<p> … </p>). By default, jsPsych centers all text, which sometimes looks fine (e.g. for the judgment trials, where we want the stimulus to be centered) but it looks terrible for instruction text, so I also tell it to left-align that text, by adding some stuff inside the paragraph tags - I start a left-aligned paragraph with <p style='text-align:left'>, then end it with </p> as usual. Finally, the choices parameter for this trial type is a list of button labels - lists are enclosed in square brackets, here the list contains exactly one option with the “yes I consent” text, which produces a screen with exactly one button to be clicked. Finally, I have to use a backslash (\) character whenever I want to include a line break in the stimulus string, otherwise javascript thinks there is a syntax error.

I also define some information screens - these are also html-button-response trials, just like the consent screen. So for example the first instruction screen looks like this:

var instruction_screen_1 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlButtonResponse,

stimulus:

"<h3>Instructions</h3> \

<p style='text-align:left'>In this experiment you will read English sentences, and determine if they sound\

grammatical to you. By grammatical, we mean whether you think a native speaker of\

English could say this sentence in a conversation. In other words, do you think it\

would sound odd for your friends to say this to you, as if they don't speak English natively?</p>\

<p style='text-align:left'>We are <b>not</b> concerned with whether the sentence would be graded highly\

by a writing teacher: we do not care about points of style or clarity, and we do\

not care about the grammar rules that you learned in school (who versus whom,\

ending a sentence with a preposition, etc). Instead, we are interested in whether\

these sentences could be said by a native speaker of English in normal daily speech.</p>",

choices: ["Click to proceed to the next page"],

};

That’s quite a lot of text, but it’s just a very simple button response trial with a long bit of HTML-formatted bit of text to display. There are several other options for instruction screens - html-keyboard-response would be OK (although I find it’s a bit too easy to advance through lots of those by mashing the keyboard), or jsPsych provides an instructions plugin which allows you to specify multiple pages in a single trial and gives participants the ability to scroll forwards and backwards through those pages.

Once all the various trials are defined, we can stick them together in a timeline for the experiment. The timeline is very simple and is just a list of all the trials we have created up to this point, in the order we want them to appear:

var full_timeline = [

consent_screen,

instruction_screen_1,

instruction_screen_2,

judgment_trial_1,

judgment_trial_2,

judgment_trial_3,

judgment_trial_4,

final_screen,

];

Then to run the experiment we call jsPsych.run with this full_timeline variable we have created.

jsPsych.run(full_timeline);

Exercises with the grammaticality judgment experiment code

Attempt these problems. After the practical you will be able to consult some notes on the answers, but note that this link won’t function until after the class - we want you to try this stuff yourself!

- How would you add extra judgment trials to this code, to ask people about the grammaticality of some additional sentences? Try adding a few new judgment trials.

- Have a look at the data that is displayed at the end of the experiment. This is in comma-separated format, so a series of columns separated by commas, the very first row of the data gives you the column names. Can you see where the stimulus and the response for each trial is recorded? Is there anything in the data you weren’t expecting or don’t understand? Tip: this can be a bit unwieldy to look at on the screen, so you might want to copy and paste it into a spreadsheet app (e.g. Excel) and look at it there. Copy the text on the screen, paste it into e.g. Excel then use the “Text to Columns” command (under the Data menu in Excel on my mac) to format it - the data is comma-separated, there is a comma between each column, so you want to select “Delimited” with comma as the delimiter. If you get that right you’ll suddenly go from a big mess to a nice spreadsheet with columns, which will help you make sense of it.

- Can you change the information screens so that participants progress to the next screen by pressing any key on the keyboard?

- Can you change the judgment trials so participants can provide a single-digit numerical response, e.g. any number between 1 and 9, rather than simply allowing y or n as valid responses? That numerical response could indicate a more continuous scale of grammaticality, a bit more like Sprouse’s magnitude estimation task.

- Can you change the judgment trials so the participants provide their responses by clicking yes/no buttons, rather than using the keyboard? (Hint: look at how I did the button on the consent screen)

- How would you use buttons to provide a wider range of responses (e.g. “completely fine”, “a little strange”, “very strange”, …)?

- [More challenging] Sprouse (2011) actually uses a rather different layout and type of response: he has participants enter a numerical value for each sentence, has multiple judgments presented on a single page, and provides a reference sentence (e.g. an example sentence which should receive a score of 100) at the top of each page. Can you replace our simple yes/no judgment trials with something more like what Sprouse did, using the jsPsych survey-text plugin?

Optional: a version of the code using timeline variables

You might have noticed that in grammaticality_judgments.js we quite laboriously lay out 4 judgment trials, all of which are identical in structure apart from the stimulus parameter. There are a couple of more efficient ways to do this, one of which is by using jsPsych timeline variables. If you’d like to see how that’s done, download and inspect the file grammaticality_judgments_with_timeline_variables.js, stick it in your grammaticality_judgments folder, then see if you can get that to run by editing grammaticality_judgments.html so that it loads the timeline javascript file rather than the basic one (by editing line 9 of the html file).

You might be wondering what the advantage is of using this slightly fancier code, and/or thinking “I could just copy and paste the judgment trials and edit them directly, isn’t that simpler?”. It maybe is conceptually simpler to copy and paste simple code, but it’s also more error prone, since it relies on you not making any mistakes in copying, pasting and editing the same little block of code over and over again. In general, if you find yourself doing a lot of copying, pasting and editing when writing code it’s a sign that you are doing something manually that the computer could do for you automatically, more quickly and with less chance of errors. We’ll come back to that in the next practical when we look at self-paced reading, where the “simple” manual approach would produce some really unwieldy code.

Re-use

All aspects of this work are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.