Week 4 practical

Collecting reaction time data, more complex nested trials

The plan for week 4 practical

This week we are going to look at code for a simple self-paced reading experiment - as you should know from the reading this week, in a self-paced reading experiment your participants read sentences word by word, and you are interested in where they are slowed down (which might indicate processing difficulties). We therefore care about reaction times (which we didn’t care about for our grammaticality judgments task last week, although jsPsych collected them for us anyway). We are also going to see some slightly more complex timelines, with trials that consist of several parts. Finally, I’ll add an example at the end of how to collect demographic info from your participants, which is often something you want to do.

Remember, the idea is that you can work through these practicals in the lab classes and, if necessary, in your own time (e.g. if you want to make a start before the lab class, or if you don’t complete the practical in the lab class) - the lab class provides dedicated time each week to focus on doing the practicals with on-tap support from the teaching team, but you may need more than the 2 hours to get these practicals done. We are happy to help with the previous week’s class if you tried to finish it off in your own time and need some help.

First: you build it!

Believe it or not, you already have the tools to build a simple self-paced reading experiment, so this week, rather than starting with us explaining how we’d do it, we want you to have a go yourself - try that, ask us for help if necessary, then after 30-40 minutes we’ll bring everyone together, see how you got on, and move on to the rest of the practical.

To help you get started, we are going to provide you with a couple of templates to fill in - an html file that loads some of the plugins you will need (but once you decide what additional plugins you need you will have to load them too), then a javascript file where you can put your own code. That javascript file includes some extra stuff (instructions and a demographics questionnaire) that we pre-built for you so you can focus on the self-paced reading part of the experiment. Don’t worry about how the demographics questionnaire works for now, that is explained when we work through our complete version of the code.

You can download the starter templates through the following two links:

Note we are calling those files “my_…” to distinguish them from the full code we’ll give you later.

These two files should sit in a folder called something like self_paced_reading, alongside your grammaticality_judgments folder from last week - so your folder will now look something like this.

This code should run on your local computer (just open the my_self_paced_reading.html file in your browser) or you can upload the whole self_paced_reading folder to the public_html folder on the jspsychlearning server and play with it there (if your directory structure on the server is the same as suggested above, the url for your experiment will be http://jspsychlearning.ppls.ed.ac.uk/~UUN/online_experiments_practicals/self_paced_reading/my_self_paced_reading.html). We encourage you to at least check you can upload the code to the server and figure out the URL, since you will need to know how to do this for the final assignment.

If you want to see what your finished experiment should look like, you can run my copy on jspsychlearning.

If you run through the experiment you’ll see that, in addition to the instructions and a demographics questionnaire at the end (which you don’t need to code up - we have provided these in the my_self_paced_reading.js template for you), the experiment consists of the word-by-word presentation of two sentences (“Which events was the reporter describing with great haste?” and “Which building were the architects featuring in the portfolio?”), each followed by a yes/no question (“Did the reporter see what happened?”, “Did the architects have a portfolio?”) - the comprehension questions are there to prevent participants just blasting through the sentence without actually reading it.

In a little more detail:

- for the word-by-word reading, the participant sees some text on screen and progresses to the next word by providing a keyboard response (the space key)

- for the yes/no questions the participant sees some text on-screen and provides a keyboard response (either the y or n key).

The yes/no questions in particular should remind you strongly of what we did last week, so you might want to start by implementing those (e.g. by copying, pasting and then editing code from last week) and then figuring out how to make further tweaks to get the word-by-word sentence presentation. Give it a go, see how you get on, and ask for help if/when you get stuck!

Our implementation of a self-paced reading experiment

As you hopefully figured out when you were trying to build it yourself, the main part of the experiment uses a plugin you are already familiar with (html-keyboard-response), so the main new content this week will be showing you how to use a little bit of javascript (an array, a for-loop, a function) to make building a complex trial list a bit easier. If you have forgotten what for-loops or functions are you might find it useful to look back through section 05 of Alisdair’s Online Experiments with jsPsych tutorial.

Getting started

You need two files for our implementation of this experiment, which you can download through the following two links:

Again, stick these in your self_paced_reading folder, alongside the files for your implementation, on your computer and/or on the jspsychlearning server.

First, get the code and run through it so you can check it runs, and you can see what it does.

Nested timelines

We’ll walk you through our implementation. We’ll start with a simple implementation that might be close to where you ended up when you built this experiment yourself, then we’ll use some tricks to streamline this.

As you may have figured out already, each individual trial in a self-paced reading experiment is actually rather complex: it involves word-by-word presentation of a sentence, followed by a comprehension question.

The way to do this in jsPsych is to have multiple trials per sentence: one trial for each word in that sentence, and then a final trial for the comprehension question. These are all type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse - for the word-by-word presentation we just want the participant to hit spacebar to progress, then we will make the comprehension question a yes/no answer (basically just like in the grammaticality judgments code from last week).

We could do this all manually, and just specify a whole bunch of trials like this:

var spr_trial_the_basic_way_1 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus:'Which',

choices: [' ']

};

var spr_trial_the_basic_way_2 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus:'events',

choices: [' ']

};

var spr_trial_the_basic_way_3 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus:'was',

choices: [' ']

};

var spr_trial_the_basic_way_4 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus:'the',

choices: [' ']

};

var spr_trial_the_basic_way_5 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus:'reporter',

choices: [' ']

};

var spr_trial_the_basic_way_6 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus:'describing',

choices: [' ']

};

var spr_trial_the_basic_way_7 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus:'with',

choices: [' ']};

var spr_trial_the_basic_way_8 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus:'great',

choices: [' ']

};

var spr_trial_the_basic_way_9 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus:'haste?',

choices: [' ']

};

var spr_trial_the_basic_way_10 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus:"Did the reporter see what happened?",

prompt:"<p><em>Answer y for yes, n for no</em></p>",

choices:['y','n']

};

If we add those 10 trials into our experiment timeline (in the correct order!) that will present the sentence “Which events was the reporter describing with great haste?” one word at a time, waiting for a spacebar response after each word, then present a y/n comprehension question at the end. This is perfectly OK and will present the sentences as intended. However, it is quite unwieldy - there is lots of redundant information (we have to specify every time the trial type, the spacebar input), building the trial list for a long experiment with hundreds of sentences is going to be very error prone, and it would be impossible to randomise the order without messing everything up horribly!

Thankfully jsPsych provides a nice way around this. A slightly more sophisticated solution involves using nested timelines (explained under Nested timelines in the relevant part of the jsPsych documentation: we create a trial which has its own timeline, and then that timeline is expanded into a series of trials, one trial per item in the timeline (so each of these complex trials functions a bit like its own stand-alone embedded experiment with its own timeline). We can use nested timelines to form a more compressed representation of the long trial sequence above and get rid of some of the redundancy.

The simplest way to do this is to split the long sequence for a single self-paced reading trial into a pair of trials: the self-paced reading part, which has its own nested timeline of several words, and then the comprehension question. That would look like this:

var spr_trial_using_nested_timeline_sentence = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

choices: [" "],

timeline: [

{ stimulus: "Which" },

{ stimulus: "events" },

{ stimulus: "was" },

{ stimulus: "the" },

{ stimulus: "reporter" },

{ stimulus: "describing" },

{ stimulus: "with" },

{ stimulus: "great" },

{ stimulus: "haste?" },

],

};

var spr_trial_using_nested_timeline_comprehension = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

stimulus: "Did the reporter see what happened?",

prompt: "<p><em>Answer y for yes, n for no</em></p>",

choices: ["y", "n"],

};

So that’s two trials rather than 10. The first trial, which I am calling spr_trial_using_nested_timeline_sentence, is an html-keyboard-response trial, which accepts space as the only valid input, and which has a nested timeline specifying the only thing that differs between the sub-trials, the stimulus - each item in the nested timeline gets the type and choices parameters from its parent, and differs only in its stimulus, so when the nested timeline is run we end up with our sentence presented in a sequence of 9 trials. Then the second trial (spr_trial_using_nested_timeline_comprehension) is the comprehension question, another html-keyboard-response trial just looking for a y-n response.

I find that quite clear to look at, but you’ll notice that there’s still some redundancy (we have to specify twice that type is jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse). Plus our overall experiment timeline is just going to be a flat list with a mix of reading trials and comprehension questions - you could imagine that if we extended that to contain e.g. 6 sentence presentations and 6 questions, and if we wanted to randomise the order somehow, we might accidentally separate a sentence and its comprehension question.

There is an even more compressed way of representing this trial sequence, which looks like this:

var spr_trial_using_very_nested_timeline = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

timeline: [

{

choices: [" "],

timeline: [

{ stimulus: "Which" },

{ stimulus: "events" },

{ stimulus: "was" },

{ stimulus: "the" },

{ stimulus: "reporter" },

{ stimulus: "describing" },

{ stimulus: "with" },

{ stimulus: "great" },

{ stimulus: "haste?" },

],

},

{

stimulus: "Was that a self-paced reading trial?",

prompt: "<p><em>Answer y for yes, n for no</em></p>",

choices: ["y", "n"],

},

],

};

So that’s a single html-keyboard-response trial which has a nested timeline; the first item in the nested timeline is the spacebar-response trials, which itself has a nested timeline, and then the second item in the timeline is a single trial with different choices, stimulus and prompt. Personally I find that slightly more confusing to look at in the code, but I like that what is conceptually a single trial - a sentence plus its comprehension question - is now a single (quite complex!) trial in the experiment.

It’s important to emphasise that these three ways of representing a self-paced reading trial all work, and look the same from the participant perspective - which one you choose might be decided by things like what you plan to do for randomisation, or how confident you are that you understand what the nested trial lists are doing!

Nested trial lists therefore make it quite easy to build a single self-paced reading trial. However, it’s still going to be a bit laborious to build a sequence of such trials. In order to build two trials we’d have to do something like this:

var spr_trial_1 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

timeline: [

{

choices: [" "],

timeline: [

{ stimulus: "Which" },

{ stimulus: "events" },

{ stimulus: "was" },

{ stimulus: "the" },

{ stimulus: "reporter" },

{ stimulus: "describing" },

{ stimulus: "with" },

{ stimulus: "great" },

{ stimulus: "haste?" },

],

},

{

stimulus: "Did the reporter see what happened?",

prompt: "<p><em>Answer y for yes, n for no</em></p>",

choices: ["y", "n"],

},

],

};

var spr_trial_2 = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse,

timeline: [

{

choices: [" "],

timeline: [

{ stimulus: "Which" },

{ stimulus: "building" },

{ stimulus: "were" },

{ stimulus: "the" },

{ stimulus: "architects" },

{ stimulus: "featuring" },

{ stimulus: "in" },

{ stimulus: "the" },

{ stimulus: "portfolio?" },

],

},

{

stimulus: "Did the architects have a portfolio?",

prompt: "<p><em>Answer y for yes, n for no</em></p>",

choices: ["y", "n"],

},

],

};

So that’s two trials that we’d add to our experiment timeline, both of which are identical in all their details except for the word list and the comprehension question. Building a long list of trials like that is definitely do-able, but is probably still quite error prone - to change the word list or the comprehension question I have to jump into exactly the right spot in the nested timelines and change the right thing, and inevitably I will forget at some point or make a mistake (I made several mistakes just doing that when preparing these notes!). Plus it’s an entirely mechanical process - if you know the sentence it’s obvious how to slot it into our trial template - and computers are good at doing mechanical stuff methodically, so it makes more sense to automate this.

What we’ll do is use a little bit of javascript and write a function (you can refresh your memory on functions from the relevant section of Alisdair’s tutorial) which

takes a sentence and a comprehension question and uses our template to build a trial. It splits the sentence into an array of words (splitting the sentence at the spaces using a built-in javascript function called split), and then uses a little for loop to build the word-by-word stimulus list. Then it slots that word-by-word stimulus list plus the comprehension question into our trial template, and returns that trial.

Here’s the function. I have called it make_spr_trial (spr = self-paced reading), and it takes two arguments (also sometimes known as parameters): a sentence to present word by word, and a yes-no comprehension question. The comments (preceded by //) explain what each line is doing, we can talk you through it in the lab if you want additional explanation! This is the first time you have seen functions used to build trials, you’ll see it every week so you will have lots of opportunities to look at this kind of thing.

function make_spr_trial(sentence, comprehension_question) {

var sentence_as_word_list = sentence.split(" "); //split the sentence at spaces

var sentence_as_stimulus_sequence = []; //empty stimulus sequence to start

for (var word of sentence_as_word_list) {

//for each word in sentence_as_word_list

sentence_as_stimulus_sequence.push({ stimulus: word }); //add that word to sentence_as_stimulus_sequence in the required format

}

var trial = {

type: jsPsychHtmlKeyboardResponse, //plug into our template

timeline: [

{ choices: [" "],

timeline: sentence_as_stimulus_sequence },

{

stimulus: comprehension_question,

choices: ["y", "n"],

prompt: "<p><em>Answer y or n</em></p>",

},

],

};

return trial; //return the trial you have built

}

Now it is very easy to build multiple trials using this function. Note that the arguments we pass in - the sentence and the comprehension question - are strings, so enclosed in quotes. We create two trials, stored in variables spr_trial_1 and spr_trial_2, that we will slot into our timeline.

var spr_trial_1 = make_spr_trial(

"Which events was the reporter describing with great haste?",

"Did the reporter see what happened?"

);

var spr_trial_2 = make_spr_trial(

"Which building were the architects featuring in the portfolio?",

"Did the architects have a portfolio?"

);

Other bits and pieces, including collecting demographics

As usual, your experiment will need a consent screen and some instruction screens. Those bits are basically the same as last week so I won’t bother showing the code here, but note that jsPsych provides an instructions plugin which might be better if you were providing several pages of instructions.

For this experiment I have also added a trial (just before our very final final_screen trial) where we collect some additional info from the participant. Often you want to collect demographic information from your participants - e.g. age, gender, whether they are a native speaker of some language - and give them the opportunity to provide free-text comments (e.g. in case there is a problem with your experiment that they have noticed). In general you shouldn’t collect data you don’t actually need - it wastes the participants’ time, potentially means you are storing unnecessary personal information about your participants, and also opens up various temptations at analysis time (“Hmm, this experiment doesn’t looked like it worked, how boring. But wait! If I split it by gender and age, which I collected for no real reason, then I get a weird pattern of significant results, maybe I can pretend I predicted that all along and publish this?”). Plus Prolific already has gender and age data for your participants (we’ll show you how to access that in the final week), so you don’t need to collect it yourself. So don’t feel you always need to include the exact questions I have put here, these are just some examples of how to collect some common response types.

The survey-html-form plugin provides a way to mix various response types on a single form - in this example I am going to include a radio-button response (select one from a number of options), a text-box response that only accepts numbers, and a larger text box for more open comments. But there are lots of other options - if you are wondering “can I do X?”, look at the documentation for the input, textarea and select tags.

We include our demographics questionnaire by creating a single trial - note that it has type: jsPsychSurveyHtmlForm, and in my html file I therefore have to load the appropriate plugin (line 8 of self_paced_reading.html does that).

var demographics_form = {

type: jsPsychSurveyHtmlForm,

preamble:

"<p style='text-align:left'> Please answer a few final questions about yourself and our experiment.</p>",

html: "<p style='text-align:left'>Are you a native speaker of English?<br> \

<input type='radio' name='english' value='yes'>yes<br>\

<input type='radio' name='english' value='no'>no<br></p> \

<p style='text-align:left'>What is your age? <br> \

<input required name='age' type='number'></p> \

<p style='text-align:left'>Any other comments?<br> \

<textarea name='comments'rows='10' cols='60'></textarea></p>",

};

The interesting stuff happens in the html parameter of this trial, so I’ll break that down for you. Once again this is a string (enclosed in double quotes) that includes some HTML markup tags. The simplest part of that is the bit of code that collects the age info:

"<p style='text-align:left'>What is your age? <br> \

<input required name='age' type='number'></p>"

So it’s a paragraph (enclosed in <p> ... </p>), and I have used style='text-align:left' to make it left-justified so it doesn’t look too awful. There’s a question (“What is your age?”), then a <br> tag to produce a line break. Then <input required name='age' type='number'> creates an input field, which will be referred to as age in our code (that’s how it appears in the results, as you will see later), and we tell it that this input is of the number type, which lets the browser know how to display it (e.g. if we swap type='number' for type='text' then you lose the little scroller to increase/decrease the number). The required flag means that this response has to be provided - your participants will not be allowed to progress unless they provide a response. You can similarly make radio buttons, check boxes and text area inputs required (in the same way, by adding this required flag), but use it sparingly - e.g. if you make an open-ended comment obligatory that is likely to annoy people.

The comments box is the same idea, but instead of using an <input> tag we are using <textarea><\textarea>. Note that there is nothing between those tags - if you put in some text (e.g. <textarea>Initial text<\textarea>) then that would appear in your text area without needing to be typed in by the participant, which is not really useful for us here. We can also specify the size of the area in rows and columns - people often take their cue about the length of the response desired based on the size of the box.

The radio buttons (yes vs no for “Are you a native speaker of English?”) are slightly more complex. The relevant part looks like this:

"<input type='radio' name='english' value='yes'>yes<br>\

<input type='radio' name='english' value='no'>no<br>"

So that is two input fields, one for yes and one for no, but they have the same name (name='english'). The browser knows in those circumstances to only allow people to select one option from among those options that share the same name. Then we have value='yes' for the yes input and value='no' for the no input - this is the response that will be recorded depending on which button the participant selects (if you leave the value bit out then the code records a very unhelpful answer of “english=on”, i.e. it just tells you that the participant answered the question but not which answer they gave). Then finally we have the text that appears alongside the button, yes and no respectively, with a <br> in between the buttons to make it look nice.

The full timeline

The full timeline for this simple 2-trial experiment then looks like this:

var full_timeline = [

consent_screen,

instruction_screen_1,

spr_trial_1,

spr_trial_2,

demographics_form,

final_screen,

];

And then we use jsPsych.run to run it and then see the data generated at the end. Next week I’ll show you how to do something a bit more useful with the data these experiments generate, i.e. save it as a CSV file.

Exercises with the self-paced reading experiment code

Attempt these problems. After the practical you will be able to consult some notes on the answers, but this link won’t function until after the class - as usual, we want you to try this stuff yourself!

- How would you add extra trials to this code, i.e. additional sentences and related comprehension questions? Is that easier using the function-based way of building trials, or the manual copy-and-paste method?

- Add another demographics question, e.g. a text box to list other languages spoken, or some additional radio buttons with more than 2 options.

- Have a look at the data that is displayed at the end of the experiment. Can you see where the stimulus for each trial is recorded? Can you see where the crucial reaction time data for each trial is recorded? Can you see how the demographics data is recorded?

- If you were going to analyse this kind of data, you would need to pull out the relevant trials (i.e. the ones involving self-paced reading, and comprehension questions). Is it going to be easy to do that based on the kind of output the code produces? How would you identify those trials? If you were particularly interested in certain words in certain contexts, is it going to be easy to pull those trials out of the data the code produces?

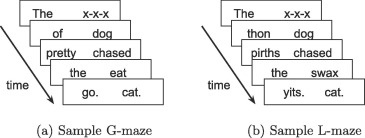

- [Optional, very challenging] An alternative to self-paced reading is the Maze task (e.g. Forster et al., 2009; Boyce et al., 2020); like self-paced reading your participants work through a sentence word by word, but unlike in self-paced reading at each step they chose one of two continuations for the sentence (see image below from Boyce et al., 2020 - G-Maze refers to mazes where the distractors are English words which would be ungrammatical continuations, L-maze has non-word distractors). Can you convert the self-paced reading code to run as a maze task? For each word presentation you will need an alternative continuation, and some way of the participant selecting their continuation (e.g. keyboard? button?). Maze tasks also don’t feature comprehension questions so you can drop those (the idea is that selecting the correct continuation throughout shows you are paying attention). Mazes also abort the sentence when the participant makes a mistake - we haven’t covered this yet and it is tricky to implement, so I would suggest skipping this feature of the maze for now, but is possible using

on_finishandjsPsych.abortCurrentTimeline(see explanation and example in core jsPsych documentation. If you decide to have a go at this task (you have been warned, it’s tricky!), you can then take a look at my thoughts on how it could be done.

References

Re-use

All aspects of this work are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.